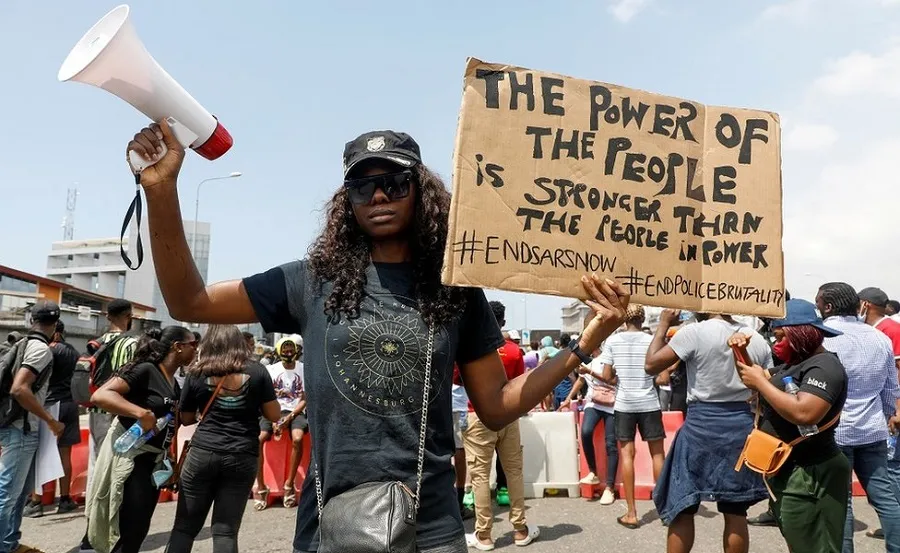

In the last week, my country has been described as being in the middle of a revolution. Nigerian youth are finding their voice for the first time and assertively taking a stand against police brutality. Spread throughout Nigeria and on social media from 8 October 2020, the #EndSARS protests reached all six geo-political regions, as well as in countries with large diaspora populations like the UK, US, Canada and Germany.

I was maybe thirteen years old the first time a Nigerian policeman threatened to slap me. I am now an adult woman and have learnt to be terrified of policemen like everyone else. I lock my doors as soon as I enter my car, not because of robbers but because one too many policemen have forced themselves inside to extort me. On unlucky days, an officer puts their hands through my lowered windows to unlock the car from within, before I have the opportunity to wind them up. They only leave after I have given them money. But all my unlucky days have been a million times luckier than thousands of others.

‘I will waste your life and nothing will happen’

Like everyone else growing up in Nigeria, I heard stories upon stories about policemen harassing, extorting, assaulting, violating and murdering citizens. I joined protests against the rape of women in police cells. I heard about the girl that was killed in Abuja. It could easily have been me. I heard about another boy who was killed, even younger than I was. I watched all the graphic videos on social media, painfully aware that incidents caught on camera were only the tip of the iceberg or, in this case, a volcano. Blood. Too much blood.

I will kill you and nothing will happen — this popular taunt by the police puts a deep fear in all of us, because we know it is true. And among the Nigerian police, a ‘special’ group called the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS) consistently won the award for Most Notorious.

The birth before the rebirths

SARS is a tactical unit in the Nigerian Police that was set up in 1992 as a response to an increase in armed robberies in Nigeria’s largest city, Lagos. Interestingly, the increase was reportedly a result of a gap in policing due to desertion following the death of a military officer at the hands of police operatives, leading to military riots. Thus, SARS is a Phoenix birthed out of the flames of police violence.

The Phoenix analogy is important as SARS has refused to cease ever since. It doesn’t matter how many fires we set, it reappears with new feathers yet the same old brutality. Today, SARS are known primarily for illegal stop and searches that violate Nigerians’ fundamental rights.

We are not all Nigerian Princes

SARS officers like to target young Nigerians, especially those with alternative hairstyles or dress sense. According to their reasoning, any young Nigerian who drives an expensive looking car or owns gadgets such as an iPhone is a Nigerian Prince or a Yahoo boy, as we say.

Let me run you through it. Imagine you’re a young Nigerian, driving down the streets of Lagos in the new car you just bought from the bonus received at the tech start up you work for. You’re chilling, cruising, playing good music when you get flagged down by SARS policemen. They look into your car, spot your computer in the backseat, then ask you to get out the vehicle and give them all your gadgets. They proceed to look through your phone and computer and everything becomes suspect — including apps like Google Hangouts. They accuse you of being a Yahoo boy and kidnap you. Yes, they can kidnap you.

I’ll cut it short. Depending on how your stars are aligned that day: 1) Your gadgets may be seized 2) You may be forced to clear out your account (either via a portable POS device or the nearest ATM) after viewing your balance through your banking app 3) You may be beaten up 4) You may be taken to one of their stations (with names like ‘Abattoir’) where you will be charged with a made up crime and forced to sign a fabricated statement 5) You may then get lost in the black hole that is the Nigerian police cell, denied the right to contact anyone, and eventually have your dead body dumped in an unknown location 6) You may simply be shot at the site of your arrest ‘… and nothing will happen.’ And if you’re a woman? It could be much worse.

Something has to happen

There’s been much speculation about what triggered the current protests. Many reports cite a video of SARS officials shooting a man dead. But the video I saw, the video that drew me into the feverish and pulsating centre of the #EndSARS movement, was a video of a woman shot by a police officer in the mouth. She was surrounded by people sitting, panting, disoriented, and there was a large hole in her face like her cheek had been carved out. I cried. It was too much.

These events have been set against a context of rising unemployment, increasing insecurity and rising inflation, following a worldwide pandemic. Public universities have also been closed as the union of its academic staff have been on strike since March 2020, leaving many students in limbo. During the pandemic lockdown period, neighbourhoods in Lagos were terrorised by gangs of armed robbers known as ‘One Million Boys’ who would rob an entire neighbourhood, systematically going from house to house, with the police often nowhere to be found, and the Anti-Robbery Squad themselves additionally terrorising innocent Nigerians.

The protests started on Twitter then seamlessly transitioned into the ‘real world’, and remarkably they continue to straddle both.

Buhari is a bad boy

The 2020 #EndSARS movement has taken on a life of its own, quite different from the initial protests under the same name in 2017. Some people think this is because it is predominantly driven by 18–24 year olds, Nigerian Gen Zs. For many, this is their first time participating actively in demanding change, bringing with them the typical Gen Z ‘take no prisoners’ attitude.

In a viral video a young adolescent girl says, ‘Buhari is a bad boy’ — referring to the current President with words that signal the height of disrespect according to Nigerian social norms. Her words have since been transformed into one of the protests’ official hashtags, in a defiant stance against the pressure placed on the youth to always hold their ‘elders’ in deference.

We dey your back

There is no place like Nigerian Twitter. We are separated into cliques and groups and sometimes engage in digital wars. One such women-led group — previously labelled the ‘feminist coven’ — rose to online prominence at the forefront of current protests by mobilising resources (about USD120,000 raised in less than a week, plus additional bitcoin) for protesters. They have arranged daily food and drinks, amassed a database of over 600 volunteer lawyers across the country working on unlawful arrests, negotiated the release of arrested protesters, arranged ambulances, settled hospital bills — in effect acting as a government. Disbursements from the protest fund are announced on Twitter, and response units have been set up to cater quickly to funding requests for planned or ongoing protests.

Responsiveness, transparency, accountability — the demands of the youth have been provided by this group of young Nigerian women. Yet the protests remain proudly leaderless, a strength that hopefully does not prove to be a weakness in the coming days or weeks. Talks about organising ‘towards 2023’, the next Nigerian elections, have also begun to take place.

Sọrọ sókè werey

A Yoruba phrase that loosely translates into ‘speak up fool’, Sọrọ sókè werey has become another iconic statement associated with the protests. It is directed at the government and the leadership of the police force, a call for decisive action to disband SARS, provide reparations and justice for victims and pursue wider reforms to eliminate police brutality.

The first announcement by the Inspector General of Police (IGP) on the ‘dissolution’ of the tactical squad was followed by police violence and brutality in many protest zones. That protesters have been killed since the announcement nullifies its credibility.

A second announcement has been made, accepting the five demands by protesters in response to the first announcement. The movement remains unsatisfied, especially by the IGP’s plans to create a new tactical team known as the Special Weapons and Tactics Team (SWAT). The announcement of a ‘new’ SARS, even before the prosecution of named SARS officials with documented cases of brutality, begs the question of whether anything has changed, especially since it follows a series of similar announcements from the last few years. Meanwhile, protesters have pledged to hit the streets until the government is able to sọrọ sókè. As a developing story, it remains to be seen whether the 2020 #EndSARS movement will finally set the country on the path to true police reform.